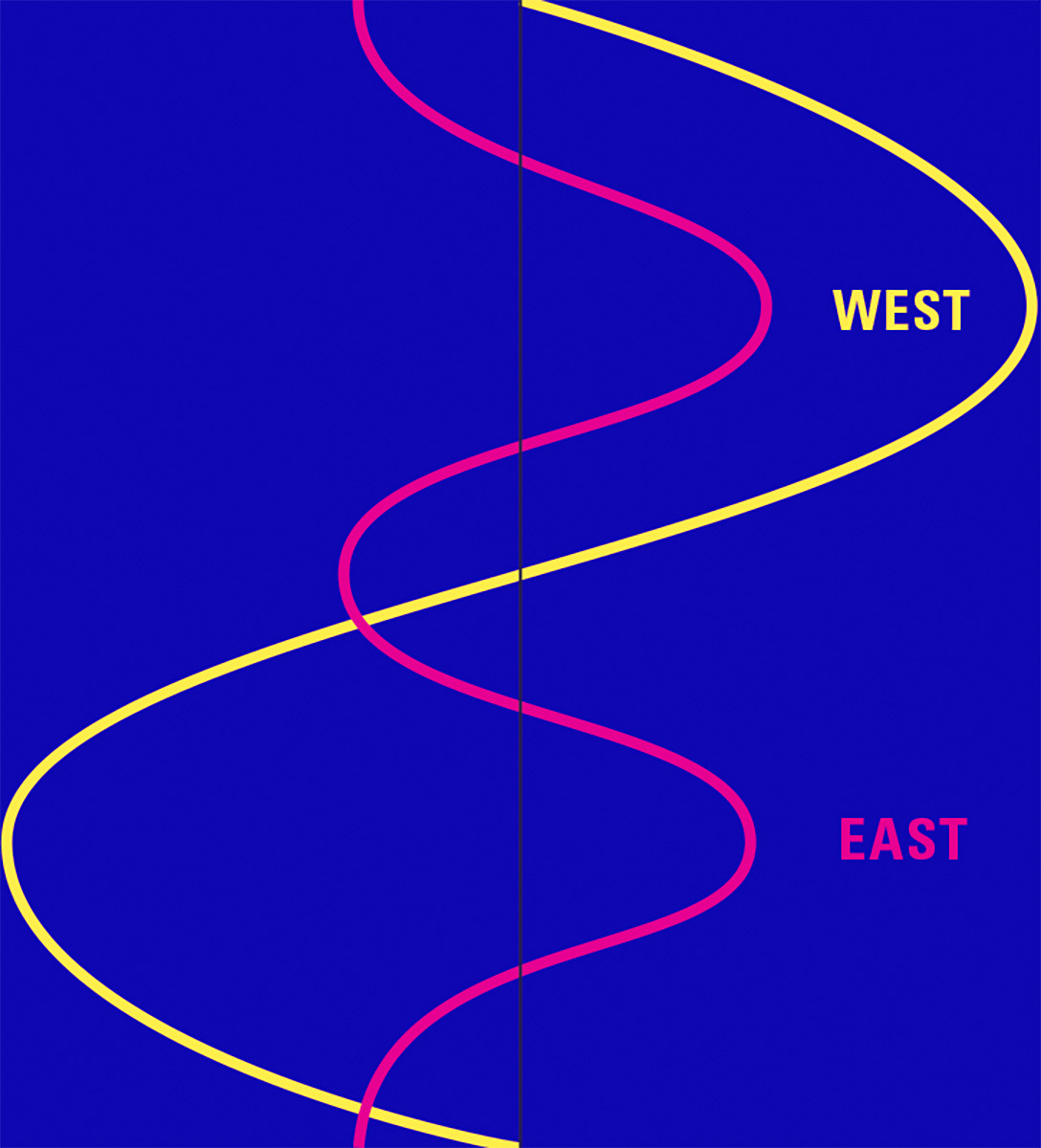

The Double Helix of Berlin Post-War Modernism

Lecture at the Copenhagen Architecture Festival 2019 CAFx

–

9. April 2019, 19 Uhr · Cinemateket Copenhagen ·

The Double Helix of Berlin Post-War Modernism

Despite the fact, that Berlin had been a divided city – since 1948 administratively, from 1961 to 1989 by the Berlin wall – it was always both, East and West. Under the patronage of the prevailing occupying powers a battle was fought for the future, for the superiority of their different social and political systems.

Architecture and urban construction played an extraordinary role in this competition. Aside from the political differences, the difference between avant-garde and tradition, inherent to modernism, formed the basis for an aesthetic expression for these political differences. Stylistic and typological differences of architecture and urban construction were enormously politically loaded. Of course, the legacy of the Bauhaus always played a role here, whether open or hidden.

This overlapping of political and aesthetic polarities and the efforts undertaken on both sides led to outstanding urban ensembles. Three unique projects of post-war Modernism are especially worth mentioning: the first stage of construction of the Karl-Marx-Allee (the former Stalinallee), the International Constructing Exhibition (Interbau) 1957 comprising of the Hansaviertel, the Academy of the Arts and the Congress Hall and as an extension the Corbusier House and finally the second stage of construction of the Karl-Marx-Allee. Berlin has decided in 2012 to nominate these three projects together for the World Heritage List of UNESCO.

Confrontation

During the mid-fifties the architectural bloc confrontation found its classic expression in Berlin: the traditionalist Stalinallee in East Berlin and the Interbau 1957 in West Berlin.

In a synchronous view Berlin’s post-war architectural heritage of the fifties and early sixties is unique in its antithetical cultural and political constellation:

Located on both sides of the Brandenburg Gate and related to the city’s great East-West axis, they represent, in unparalleled conciseness, concentration and quality, two internationally relevant post-war tendencies in architecture and urban design, each promoted by corresponding occupying powers: the eastern model referring to regional-historicist building traditions in accord with Stalin’s slogan «socialist in content, national in form», and the western model of the International Style.

We see the dualistic structure: The alleged continuation of the Bauhaus as «International style» in the West, Soviet inspired neo-classical architecture in the East, an open urban landscape loosely set in parks and greens in the West and imperial axes in the East, the «open society» in the West and the «totalitarianism» in the East.

This good old Cold War pattern offers us, however, only a characteristic snapshot of the history but not a full comprehension of the history.

Competition

Taking a more diachronic view allows us to see that this very special confrontation in Berlin has its own historical structure:

It’s a dialogic structure, a structure of construction and counter-construction, of thesis and anti-thesis.

The early post-war period after 1945 was characterised internationally by a new approach to Modernism. Especially in countries that had the chance to continue the modern architecture of the inter-war period, like Scandinavia, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Austria, the Netherlands or Yugoslavia, and in countries where modern architects were repressed or fought in the resistance against German occupation or went to exile, post-war modernism was strong. The attitude aimed at a radical renewal of the concepts and experiences of the 20s and 30s following the CIAM declaration of the Athens Charter. Also, in East Germany many modern architects, among them not a few Bauhäusler (former member of the Bauhaus) hoped to continue their work, free of nationalist and racist barriers of Nazi-ideology.

Early plans for Berlin also started in this way. The first Berlin councillor for construction and urban planning, appointed by the Soviet administration, was Hans Scharoun. His so called «Collective Plan» of 1946 followed the idea of a linear city and the CIAM principles. The first plannings for the Stalinallee were also inspired by Ludwig Hilbersheimer and Le Corbusier. Hermann Henselmann designed modern types of dwelling, row houses and detached houses or solitaires. But, the «Wohnzelle Friedrichshain» (residential area) designed by Hans Scharoun remained a fragment. In the Karl-Marx-Allee only the characteristic houses with balcony access (and some multi-story residential buildings in the background of the boulevard) bear witness of early post-war Modernism .

And this was not an exception. There was a really broad movement of modernist architecture in East Germany immediately after the war. [Andreas Butter]

The big break came in 1950. After a journey of East-German architects to Moscow in the Spring of 1950 modern architecture, Bauhaus and the CIAM-concept were condemned by condemned by the political leaders as «imperialistic», «cosmopolitan», «western decadent», «alien to the people» and «anti-socialist». At the same time in all countries of the Eastern bloc the installation of Stalinist party dictatorships led to nationally formed architectures.

In East Berlin Hermann Henselmann designed the new image of the requested «Neue Deutsche Baukunst” with his «Haus an der Weberwiese», which served as the model for the first stage of construction of what was then still called Stalinallee.

With the construction of the «First socialist street of Germany» with it’s «Residential Palaces for Workers» the East German leadership sent a strong signal to both East and West and initiated the cross-border rivalry of architecture and urban planning in the field of residential houses and areas.

It took some time until the West was able to respond. The first projects of social housing estates in the West, such as the settlements «Ernst Reuter» (1953-1955) and «Otto Suhr» (since 1956), named after two West Berlin politicians, were located at the sector borders to East Berlin and could not achieve any significance for the whole city.

This was only accomplished by the International Construction Exhibition 1957, which was planned and realised as the counter-project to the Stalinallee. As an open urban landscape the settlement was built on the ruins of a 19th century housing area, which was destroyed during the war, located at the northern edge of Tiergarten, near the East-West-axis, which after the workers’ uprising in Stalinallee in 1953 had been re-named «Street of the 17th of June». The West Berlin project succeeded to recruit internationally well-known architects and to create a great variety both of floor plans for flats (such as maisonettes, flats with so-called all-rooms like as main halls) as well as a variety of house types (such as raw buildings, high rise blocks and detached family houses in carpet settlements).

Against the symmetry of the great axis of Stalinallee and the richly decorated Residential Palaces, the Interbau 1957 displayed variety and the individuality of living in a functional architecture. The little shopping-centre, the library, two churches and finally the Academy of Arts, the Congress Hall (the American contribution) and the Unité d’Habitation Type Berlin by Le Corbusier (outside from the inner-city Hansaviertel), completed the Interbau 1957 programmatically as the «City of the Future».

After the death of Stalin in March 1953 the Soviet Union (1954) and later the other East European countries returned to modern architecture and urban design, based on an extensive industrialisation of the building industry.

The first and in a certain way best project of the return to modern architecture in the German Democratic Republic was the second stage of construction of Karl-Marx-Allee at the end of the fifties.

Continuing the idea of the great boulevard, the new stage of Karl-Marx-Allee represents a convincing eastern answer to the Interbau project. It marked the dawn of a new era. The decoupling between the residential buildings, made from prefabricated slabs, and the special pavilions, the rhythm of special public buildings with their own architecture presaged a new mobility and freedom of objects and people in urban space. Although the politburo of the state party refused solitary high-rise buildings as individualistic and too close to the Interbau high-rise buildings, the new Karl-Marx-Allee has many similarities with the Interbau complex.

For example the entrances to the subway situated in pavilions, the green loosened urban landscape and equipping the residential areas with public institutions.

Co-Evolution

Historically, criticism of Modern Movement and International Style architecture and urban design coincided with the political collapse of the GDR and the Eastern Bloc. So, after 1990 postmodern Zeitgeist criticism concentrated on GDR Modernism, while the architecture of the early GDR found rapid acceptance. In an exact reversal of the political and aesthetic confrontations of the 50s, the «old» Karl-Marx-Allee in East Berlin gained wide recognition in the field of building culture as a «European boulevard», and was restored according to the guidelines for historical monuments shortly thereafter. The Hansaviertel (Interbau 1957) and the «new» Karl-Marx-Allee, on the other hand, had to withstand the anti-modern Zeitgeist for several years from 1990 onward. In the meantime, however, many of these historic monuments have been restored as well according to listed property requirements, and their value as building culture is recognised.

Today we have the opportunity to understand and appreciate this Berlin heritage, born from the political confrontation between East and West and the aesthetic confrontation between SocRealism and International Style, as a shared built heritage of Eastern and Western Europe and as part of a universal cultural heritage. This reciprocal and characteristically delayed intertwining of East and West and historicism and modernism can be associated with the image of the «Double Helix». In a manner of speaking, Karl-Marx-Allee (old and new) and Interbau store, in the logic of their creation, the architectural and urban design code of Berlin’s post-war development.

What was once built as confrontational urban design and expressed implacable competition can be discovered and made accessible in the reunified Berlin today as a joint cultural heritage of the (formerly divided) post-war Europe. Today, that means after the era of confrontation between the systems has ended and with a critical look at both the International Style and its counter-movement of regional historicism.